We don't know shit about how businesses are founded

August 2022

You might have heard about how Reed Hastings was driven to start Netflix after being hit with a $40 late fee from Blockbuster Video.

Maybe you read it in Vanity Fair, or Fortune.

Maybe you’re one of the 1,538,339 people who have watched this dramatic YouTube video about it, or one of the 19.9 million people who follow Netflix on Twitter.

Doesn’t matter where you heard it, because it’s not true.

Not true, but according to Hastings’ cofounder, “it’s a good story, and Netflix is a story, so I’m okay with that.”

Should you be okay with it, though?

Aside from taking up space in your brain, lies stories like this work to gently distort your perception of reality. In fact, that’s the whole point of them.

More on that in just a moment, but first - some more good stories.

How about the inspiring tale of two genius tech nerds founding a company in their garage? Get this - they’re both named Steve! So quirky.

Anyway, the Steves’ garage project went on to be worth trillions of dollars, bringing you the iPhone, the iPad, and the FireWire cable.

Love that story! It’s not true, though.

And if you’ve heard about how Elon Musk founded Tesla because, as a visionary engineer, he refused to believe that electric cars should compromise on performance, well …

- He didn’t found the company

- He came on board as an investor, not an engineer

- He won the right to call himself co-founder in a lawsuit

Why is this a thing?

No doubt there’s some degree of innocent “tech bro wants everyone to like him” motivation behind the creation and propagation of these myths. But the $6.6 billion dollars poured into public relations each year is a strategic investment.

If you imagine these organizations as being led by plucky underdog genius visionaries, you might not give credence to stories about their use of child labor or racist work environment. You’re less likely to be offended by simple price increases, too.

What should we do, then?

Given the proliferation of bullshit surrounding corporate origin stories, a reasonable policy would be simply to treat them like entertainment - no matter what the story, or where it’s being reported.

Dismiss out of hand the myth of the brilliant founder who built an empire out of a clever idea and a bit of elbow grease. That’s just not how it works.

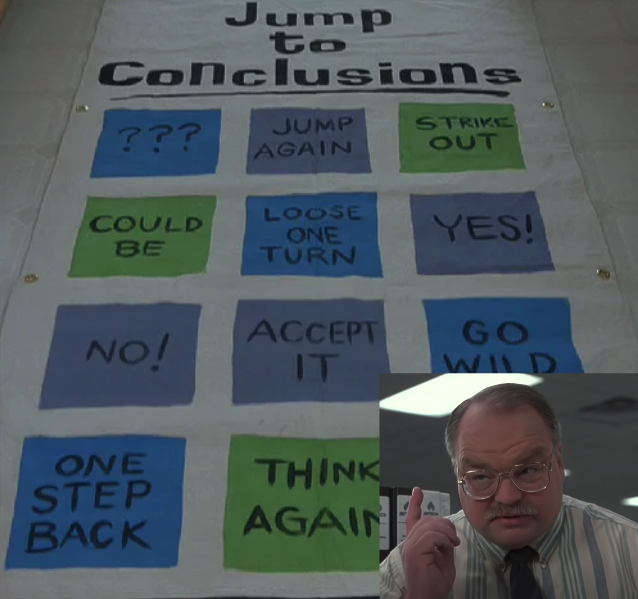

You need more than an idea. Ideas are cheap. This guy had an idea, but there’s no version of reality in which the Jump to Conclusions Mat becomes a multi-trillion dollar company.

If you want to bring a bit more nuance to how you process corporate folklore, a good rule of thumb is to ask yourself:

If I knew that the company’s leadership paid to write this news article and put it in my feed, would I still trust it?

Quarterly earnings report, or plans to open a new facility? Probably legit. Story about their groundbreaking cultural innovation or the peerless genius of their CEO? Not so much.

And this approach of asking “who paid to put this in front of me?” applies beyond the realm of startup origin stories, too - as we’ll see when we look into health and nutrition research.