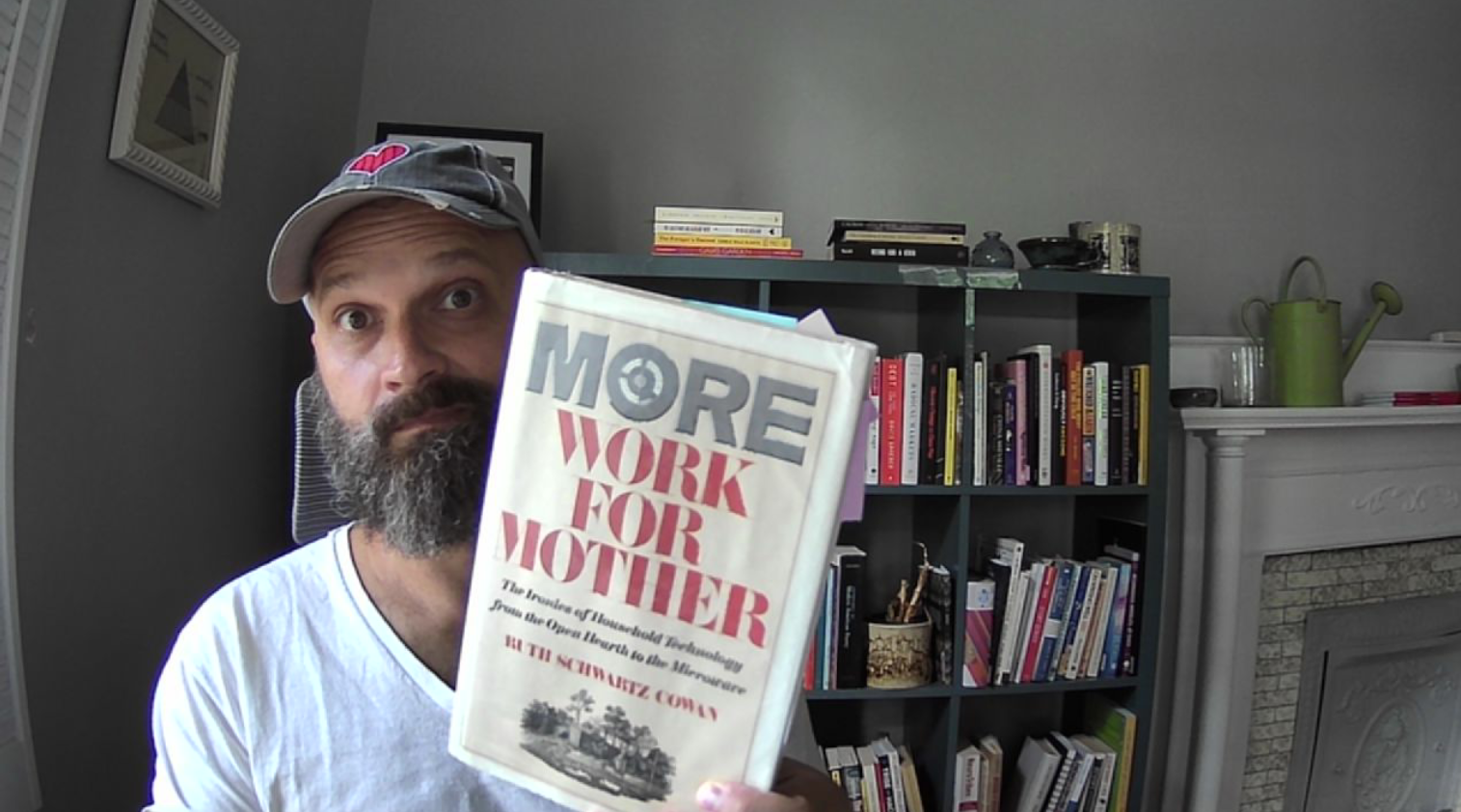

Book review: More Work for Mother

June 2023

Recommended: Yes

Why read it? It’ll change the way you think about technology. (Unless you already identify as a Luddite. Then it’ll just give you lots of fascinating historical context.)

Notes:

Modern housework depends upon nonhuman energy sources, just as advanced industrial manufacturing systems do.

Helpful reminder! Also she wrote this in 1983, before there was nearly so much concern over “nonhuman energy sources.”

… despite the diversity of what is available for purchase, almost nothing that we buy has been made “for us,” to fit special needs that we may have.

Rather than being homemade (as was customary before, say, the 1800s), our tools are mass produced and way too complex for us to understand or repair ourselves.

More people spend their days engaged in housework than in white collar or blue collar work. The (unpaid) homemaker labor force is the biggest single labor segment in the nation, interesting.

Fundamental thesis: Advances in technology don’t necessarily reduce labor, but they change and redistribute it.

As an example, consider cleaning a rug. Pre-vacuum cleaner, this involved one person (maybe a man) taking it outside and one person (maybe a child) beating it with a broom … maybe once per season.

Post-vacuum cleaner, it involves one person (probably mom!) vacuuming the rug … maybe weekly.

You could say that the latter is easier and faster, but …

Easier for whom? Faster for whom? Under what conditions?

This is the question the book asks over and over. We should keep asking it!

The term “housewifery” goes back to the 1200s, but common usage of “husband” and “housewife” appear as the capitalistic organizatoin of society takes hold, and “housework” is first used in the mid 1800s, when industrialization began in the US and England.

This era saw gender roles take shape—the home is the woman’s sphere, work is the man’s sphere. (Before that, both would typically work the land cooperatively, regardless of how labor was divided.)

Some historians have also suggested that these new sets of social definitions served the interests of certain powerful segments of society: manufacturers who needed markets for the goods they were producing, mill owners who needed tractable workers for their factories, ministers who needed audiences for their sermons, political leaders who needed to stabilize their electorates, and the newly rich men who needed to be able to cement their status with the mortar of elaborate hospitality that only homebound wives could provide.

Wild to think that just 200 years ago the idea of being a “consumer” was … not a thing. Maybe you purchased tools, pots and pans, coffee, etc. but not much more than that.

Pre-1900s, most people ate a very plain diet.

… bread, cheese, butter, porridges, eggs, raw fruits and vegetables in season, preserved fruits and vegetables out of season … all of it washed down by beer, cider, milk, tea, or coffee …

Hmm IDK I see what she’s saying, but isn’t 80% of the food in the grocery store made out of corn and soy? Which diet is more varied?

In the 1700s, the odds of getting by as a lone farmer were pretty low, whether you were a man or a woman.

Small sonder that most people married and, once widowed, married again.

Ready-made cloth is an industrial invention, dating back to the 1800s. Before that, each household would have spun and woven its own fabric.

Early 1800s life: You head to the mill with your grain, planning to be back by sundown, but you are somehow hindered, so the family goes without bread till you return.

White bread is highly refined and pre-industrialization, it was extremely rare to come by. Enjoyed by the rich and folks on long voyages (because it doesn’t spoil). As industrial mills started springing up, it became cheaper and was immediately seen as a status symbol.

Imagine Wonder Bread being a signal of wealth. Stranger than fiction.

The egg beater was invented in the mid-1800s. Makes it way easier to beat eggs! But it also led to an increase in popularity of angel food cakes, which are twice as much work as traditional cake.

The stove! Cast iron cooking stoves came into popularity during the 1800s. Before that—50 years before that, 500 years before that—cooking took place over an open hearth.

Here’s a passage from an “early historian of the stove industry” …

When stoves were first introduced, a feeling of unutterable repugnance was felt by all classes toward adopting them and they were used for a generation chiefly in school houses, courtrooms, bar-rooms, shops and other public and rough places.

Kinda silly and at the same time I get it—cooking over an open hearth is a different vibe from cooking over a huge iron stove.

But the key point is that stoves, with multiple burners which can be kept at different temperatures, lend themselves to the preparation of more elaborate meals. Instead of stew and bread, you’re now cooking multiple courses, all while maintaining the fire and temperature within the stove. And keeping the stove clean! More work.

Stoves are more energy-efficient, so they do save labor. But only the labor of cutting, hauling, and splitting wood. Which was typically male labor.

Virtually all of the stereotypically male household occupations were eliminated by technological and economic innovations during the nineteenth century, and many of those that had previously been allotted to children were gone as well.

Specifically: leather working, whittling, carrying water, butchering.

We went from candles to gas lamps, which meant going from candlemaking to … cleaning gas lamps.

Canned foods!

The total national output of canned goods was only about five million cans in 1860 but, by 1870, was up to thirty million, and by 1880, had increased fourfold. By the turn of the century, canned goods were a standard feature of the American diet: women’s magazines contained advertisements for them on nearly every page, standard recipes routinely called for them, and the weekly food expenditures of even the poorest urban families regularly included them.

Not just cans!

Indeed, by the end of the [19th] century, processed foods of all kinds—packaged dry cereals, pancake mixes, crackers and cookies machine-wrapped in paper containers, canned hams, and bottled corned beef—were part of the staple output of some of the largest, and most monopolistically organized, business enterprises in the nation.

Late 1800s to early 1900s saw huge changes in women’s fashion.

the Sears Roebuck catalog, for example, did not contain a single item of women’s clothing in 1894; but by 1920 it had ninety illustrated pages of female attire.

Fashion itself changed to accommodate mass production of clothing - blouses and skirts over dresses.

By the mid-1900s you could buy in a store most of what was produced at home just a hundred years prior. But this meant driving to the store, shopping, and waiting in lines, which became a central responsibility of the housewife.

Bathrooms with running water were prevalent by the 1920s.

In 1907, only 8% of households were wired for electricity. By 1920, it was 35%.

Gas heating and cooking were heavily subsidized, with stoves being given away at one point. (This was to compete with electricity.)

This quote sums up the core thesis of the book:

Washing sheets with an automatic washing machine is considerably easier than washing them with one that has a wringer, itself considerably easier than washing them with a scrubboard and tub. Yet the easiest solution of all (at least from the point of view of the housewife) is to have someone else do it altogether—common practice in the nineteenth century and even in the first few decades of the twentieth … the woman endowed with a Bendix would have found it easier to do her laundry but, simultaneously, would have done more laundry, and more of it herself, than either her mother or grandmother had.

She paints a picture of the technological marvels we might have enjoyed—apparently gas-powered refrigerators are way more efficient and reliable, but the dominant manufacturers (GE, GM, Westinghouse) were invested in electric fridges and so dominated the market.

Consumer “preference” can only be expressed for whatever is, in fact, available for purchase …

also

General Electric became interested in refrigerators because it was experiencing financial difficulties after the First World War and needed to develop a new and different line of goods. G.E. decided to manufacture compression, rather than absorption, refrigerators because it stood to make more profits from exploiting its own designs and its own expertise than someone else’s.